Music on the brink

As the fifth Carthage faculty member ever to receive a Fulbright Scholar award, Prof. Dennee conducted a seven-month research project in Tanzania last year. To keep the region’s traditional music alive, he compiled a comprehensive set of classroom resources for teachers there, here, and everywhere.

Although he genuinely enjoyed teaching classes and conducting a choir at Tumaini University Makumira, “TGIF” still applied. On Fridays, he got the bulk of the legwork done.

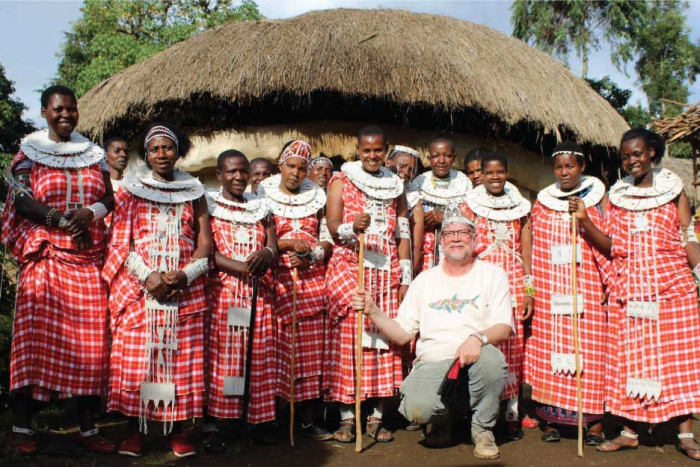

That’s the day each week when Prof. Dennee, along with a translator, would hop in his 2003 Toyota RAV4 for a road trip to the foothills of either Mount Meru or Mount Kilimanjaro. He visited musicians from indigenous groups — primarily the Meru, the Chagga, and the Maasai — and recorded their performances.

Most of the traditional singers they met were elders. Aside from the Maasai, whose connection to their musical roots remains strong, interest dwindled with each passing generation. Kids prefer the latest hits.

Still, it lended an urgency to the project. Prof. Dennee hates to watch entire categories of artistry fade away.

“It’s like an animal going extinct. Our world is changed forever, and not for the better,” he said. “This is one way to keep both the music and the language alive.”

Rather than futilely trying to reverse a worldwide trend, the visiting Fulbrighter set out on a more bite-sized quest: to salvage the rich vocal and instrumental legacies of a few cultures he knows and admires.

Sounds of the world

A musical omnivore, Prof. Dennee listens to “just about everything,” like the CD of world music chart-toppers and new releases that comes with each issue of Songlines magazine.

That enthusiasm shows up in the Global Music Education class he teaches at Carthage.

That worldview crystallized over time. Tours of Europe with his high school band — young Peter played the euphonium — and the Carthage Choir got the wheels turning.

“I’m really into being a citizen of the world,” he said, “and understanding people’s music is one way of getting to that.”

Working in the Milwaukee Public Schools early in his career, Prof. Dennee started looking for a global music curriculum. All he found were poor imitations of multicultural music from Americans.

“It has to be authentic,” he said. “Back in 1990, that was hard to find.”

Well, what’s more authentic than seeing a culture in person? Joining the faculty at his alma mater in 2005 opened a promising new door in the search.

Carthage consistently ranks in the top five nationally for participation in short-term study abroad, and few faculty members lead more J-Term study tours than Prof. Dennee.

In most years, after wrapping up his duties as director of the annual Carthage Christmas Festival, he has just enough time to exhale before heading to the international terminal. His favored destinations are clustered in Africa.

First came Namibia, a somewhat hidden gem on the southern end of the continent where English is the national language. Since forming a lasting connection with the Oonte Centre for Orphans and Vulnerable Children in 2010, he’s raised thousands of dollars for it. J-Term students carry out service-learning projects at the center.

When the same travel agency offered a deal to Tanzania, he became intrigued with the East African country. More than 120 tribes contribute to a remarkably diverse cultural mosaic.

This is Prof. Dennee’s third visit to Tanzania. After scouting the location in 2016, he led the Carthage Treble Choir on tour in 2019 to perform for — and learn from — the welcoming residents.

Those existing relationships made it easier for the visiting scholar to hit the ground running when he returned this year.

A delicate balance

The chance to create a world music curriculum appealed to Ms. Taylor, an aspiring music instructor. Awarded a Summer Undergraduate Research Experience grant before her senior year, she collaborated with Prof. Dennee to create a Meru music teaching guide.

No, Ms. Taylor didn’t get to visit the republic she studied so closely from afar, but their work set the stage for the more expansive Fulbright project. It also gave her plenty to consider.

“Developing resources about another culture’s music highlighted the importance of cultural sensitivity and respect,” she said. “There is a very fine line between appreciation and appropriation that, as a future educator, I need to be mindful not to cross.”

“I’m not making their music mine,” says Prof. Dennee, explaining the distinction. “I’m celebrating it.”

The carefully edited videos will show musicians singing in their tribal languages while dancing and playing instruments. Musical notation, translated lyrics (in English and Swahili), and lesson plans will be available separately.

In a normal year, the fellowship spans 10 months, but the Fulbright Program’s COVID-19 restrictions left Prof. Dennee in a holding pattern throughout last fall. Finally cleared to make the trip, he arrived in Tanzania in early January 2021, but more obstacles emerged.

Shortly after he settled in at the university, a health scare unrelated to the pandemic threatened to cut the residency short. Prof. Dennee lost 40 pounds in a matter of days before a visiting doctor diagnosed the mysterious illness as an ulcer.

Concerned students brought food to the house while he was laid up. To their relief, the professor they address as “Sir” returned to work after missing just three days of classes.

The road trips resumed, too.

“We end up going places where cars have never been,” said Prof. Dennee. “We just kept driving until my car couldn’t go any farther.”

And then some. Bogged down in a remote area on one harrowing trip, the researchers paid local residents to dig out a 50-foot path so their vehicle could connect to an actual road.

A lighter wallet and some mud-soaked clothes seems like a small price to pay for the privilege to document vocal and instrumental styles that are found no place else.

“Each one of these groups has their own distinct way of making music,” said Prof. Dennee.

His checked baggage on the return flight reflects that. A craftsman from the Iraqw tribe hand-made a couple of string instruments for him using local materials like gourds, agave stalks, and goatskin. Prof. Dennee also bought a long, narrow Chagga drum and some ankle bells.

Thankfully, some of the most valuable artifacts take up no space in a suitcase. Intangibles like deeper cultural understanding will guide his work as director of Carthage’s new African Studies Program.